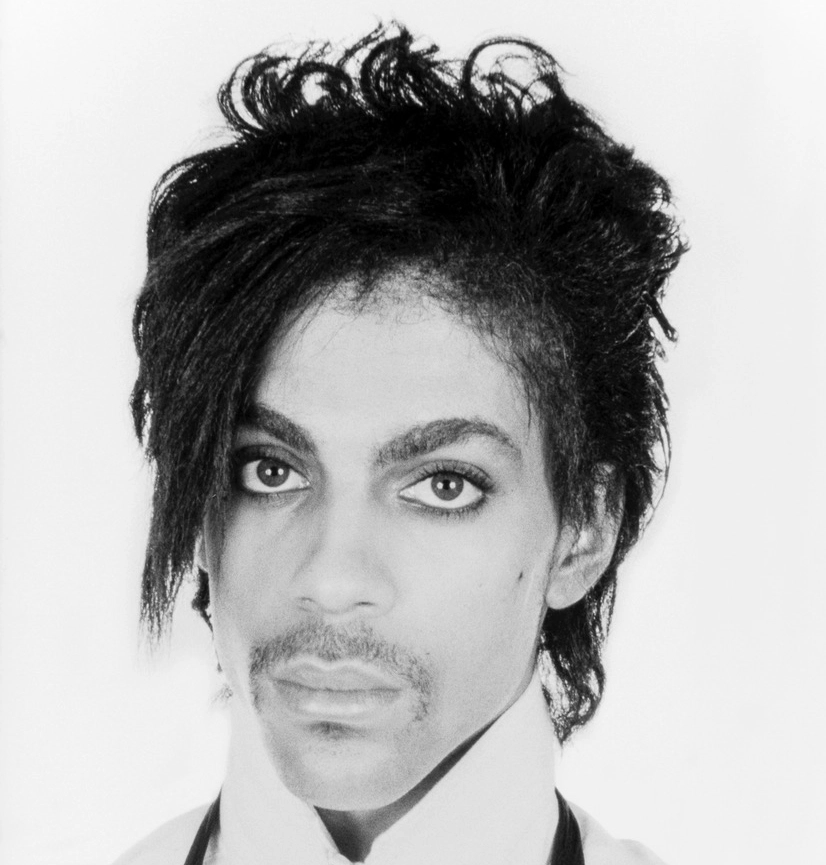

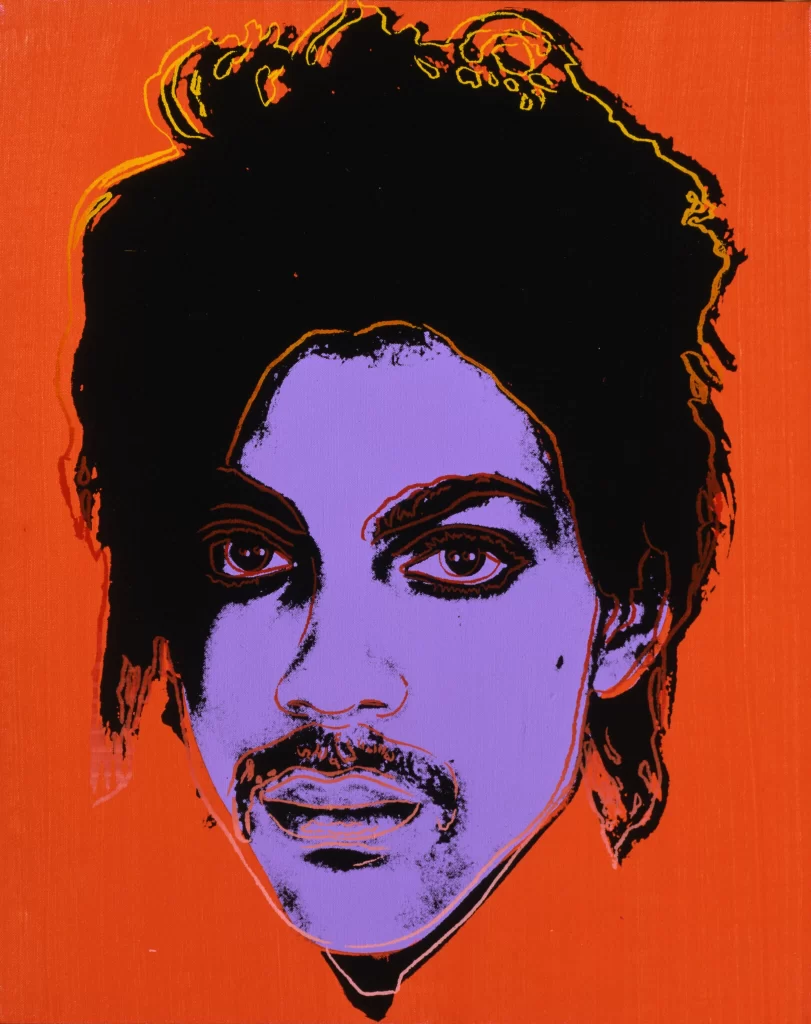

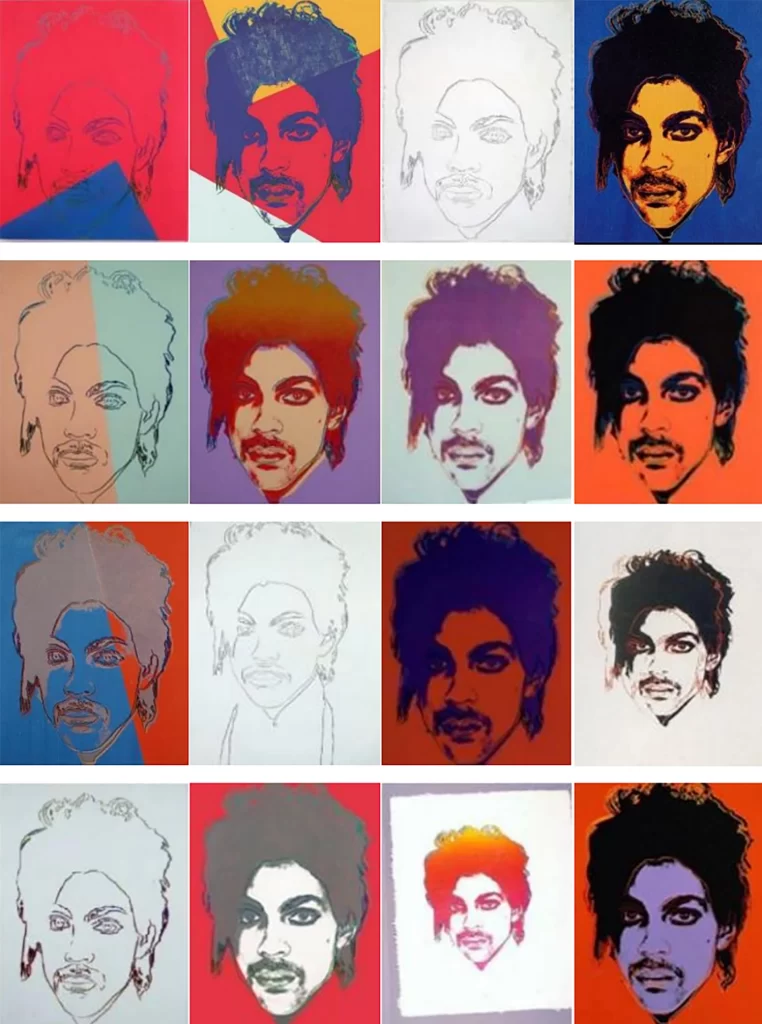

In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith photographed the music artist Prince for Newsweek magazine. 15 years later, she licensed one of those photos to Vanity Fair as a single-use artist’s reference for an illustration. The artist was Andy Warhol and he created his purple silkscreen portrait of Prince from Goldsmith’s photo. Later on, without Goldsmith’s knowledge, Warhol created a series of Prince silkscreens.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair approached the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) for a license to use one of the silkscreens, Orange Prince, for a commemorative edition of the magazine. When the magazine came out, Goldsmith became aware of the existence of Warhol’s Prince Series and sent AWF an infringement letter. AWF returned the favor by suing Goldsmith for a judgment of non-infringement under fair use.

Fair use permits a party to use a copyrighted work without the owner’s consent for purposes like reporting, teaching, or research. Each case must be decided on its own merits, but there are some general guidelines.

Factor 1 is the purpose and character of the use; is the work commercial or non-commercial, and is the use transformative- meaning it adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.

Factor 2 is the nature of the copyrighted work

Factor 3 is the amount used

Factor 4 is the effect of the use on the market

While fair use wasn’t limited to usage only in criticism, comment, reporting, teaching, etc…these examples represent the types of copying that the courts found to be typical of fair use.

However, in the 1994 landmark “Pretty Woman” case, the Supreme court, held that 2 Live Crew’s use of Roy Orbison’s song was fair use because it was transformative. It “added something new with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” After that, the transformative nature of the work took on more importance, and artists have used the transformation standard to guard against infringement claims.

In the current case, the District Court originally decided in AWF’s favor, but the Court of Appeals reversed the decision to favor Goldsmith.

The sole question before the Supreme Court was whether “‘the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes’, weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.”

The current Supreme Court expressed no opinion on Warhol’s Prince series. But the Court noted that in the Vanity Fair Prince issue, both the original photo and Warhol’s subsequent art were both used for similar purposes: “portraits of Prince used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince”, and to the point, “the copying use is of a commercial nature”. At least in this usage, whatever transformative effects AWF might claim about Orange Prince aren’t enough to overcome having stepped on Goldsmith’s commercial toes.

Perhaps the Supreme Court’s decision here will restack the priorities of Fair Use and move the commercial effect up in importance.

Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 photo of Prince.

Andy Warhol’s purple silkscreen print of Prince.

Warhol’s Prince series of silkscreens.