Why Inventors Should Care About the Blue Buffalo Decision

If you’re an inventor thinking about filing a patent, here’s a recent Federal Circuit decision you should care about—In re Blue Buffalo Enterprises (Fed. Cir. Jan. 14, 2026). Not because it changes the law (it’s nonprecedential), but because it exposes a trap that patent drafters fall into all the time.

The trap? Two innocent-looking words: “configured to.”

How “Configured To” Claim Construction Can Undermine Your Patent Claims

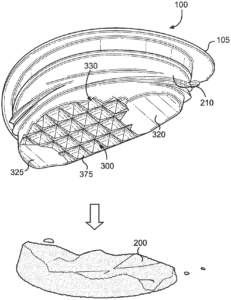

Blue Buffalo’s patent application claimed a pet food container with sidewalls “configured to be readily deformable” and a built-in tool “configured for” breaking up or tenderizing food. That sounds reasonable and it sounds structural. It also sounds like smart patent drafting. The problem is how courts usually read that phrase.

Federal Circuit Interpretation: “Configured To” Means “Capable Of”

The Federal Circuit said, once again: unless your specification clearly says otherwise, “configured to” means “capable of,” not “specifically designed to.” And that difference can make or break your patent.

Structure Over Intent: Why Patent Claims Are About the Thing, Not Your Thoughts

Here’s why.

Patent claims—especially product claims—are about structure, not intent. Courts don’t ask what the inventor meant to build. They ask what the thing is. If a prior art product can do what your claim says—even if it was built for a different reason—it can still knock out your claim.

Chief Judge Moore’s Explanation at Oral Argument

Chief Judge Moore nailed it at oral argument. Paraphrasing: if a structure “happens to actually do that,” that’s good enough. You don’t get extra credit because you intended it to do so.

That’s a big deal for inventors, because many applications quietly rely on “configured to” as a kind of magic phrase—hoping it will smuggle design intent into the claim without saying so explicitly. Courts are not buying it.

Why Blue Buffalo’s Argument Failed

Blue Buffalo tried to argue that “configured to” should mean “specifically designed to.” The judges were unimpressed. Why?

Because that would turn every patent case into a mind-reading exercise: What was the designer thinking? What was the manufacturer’s intent? That’s not how patent law works. Infringement is strict liability. Intent doesn’t matter.

How Prior Art Defeated Blue Buffalo’s Claims

So how did Blue Buffalo lose? Once the court adopted the “capable of” interpretation, the prior art fit the claims. Blue Buffalo even admitted that under that construction, the obviousness rejection stood. Game over.

Inventors often point to older cases like Aspex Eyewear and Giannelli and say, “See? ‘Configured to’ can be narrower.” True—but those cases had something Blue Buffalo didn’t: specific, concrete disclosures showing what about the structure made it especially suited for the function. Not just that it could do it, but why it did it that way.

Lesson for Inventors: Be Specific About Structure, Not Just Function

Here’s the lesson—and it’s an important one.

If a feature really matters to your invention, don’t just say it’s “configured to” do something and hope for the best. Explain what about the structure makes it work. Geometry. Placement. Relationships between parts. Physical constraints. Those are the things that earn you a narrower, more defensible claim.

The Risks of Vague Functional Language

Yes, being specific can feel risky. One reason “configured to” became popular was to avoid narrow means-plus-function claims and keep room for future variations. But vagueness has its own cost. Broad, fuzzy claims are easy to invalidate.

Blue Buffalo’s Key Takeaway for Patent Drafting

Blue Buffalo doesn’t rewrite patent law. But it reinforces a reality inventors need to understand early: functional language without structural support is a fragile foundation.

If you want “configured to” to mean more than “capable of,” you have to earn it in the specification. Otherwise, those two little words may end up configuring your patent application straight into a rejection.

Want to see some related articles on patent claims? These articles might interest you:

What Did Those Claims Consist of?

Jazz Loses the Tune: Courts Strike a Sour Note on System Patents

Patent Like You Mean it, But Also Show the Structure