NEWS

Apple v. Squires: The Federal Circuit Confirms the Director’s (Nearly) Unlimited IPR Discretion

On Friday the 13th, the Federal Circuit turned what began as a procedural APA challenge into something much larger: a precedential confirmation that the USPTO Director possesses extraordinarily broad discretion over whether to institute inter partes review (IPR).

In Apple Inc. v. Squires, the court did far more than uphold the now-obsolete NHK/Fintiv framework. It effectively declared that the Director’s institution authority is constrained only by the Constitution — or by whatever limits the Director chooses to impose on himself.

The Origin: NHK and Fintiv

The controversy began when former Director Iancu designated as precedential two PTAB decisions:

Together, those cases established six non-exclusive factors — the “Fintiv factors” — guiding discretionary denial of IPR when there is parallel district court litigation. The factors emphasized judicial efficiency, trial timing, overlap of issues, and related considerations.

Apple and several other technology companies challenged the adoption of these factors, arguing that the USPTO violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) by failing to use notice-and-comment rulemaking.

The Statutory Wall: “Final and Nonappealable”

The challenge ran into 35 U.S.C. § 314(d), which provides that institution decisions are “final and nonappealable.”

The Supreme Court has interpreted that language broadly in:

- Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee

- SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu

Those decisions make clear that the Director’s choice whether to institute IPR is largely insulated from judicial review.

Initially, the district court dismissed Apple’s case as unreviewable. The Federal Circuit briefly revived it — but only on a narrow procedural question: whether adoption of the Fintiv factors required notice-and-comment rulemaking. Substantive review of institution discretion remained off the table.

The Critical Reframing: “Instructions,” Not Rules

On remand, the district court held that the Fintiv factors were exempt from notice-and-comment rulemaking because they were not “substantive rules.”

When the case returned to the Federal Circuit in Apple v. Squires, the panel took an even more consequential step. It reframed the Fintiv factors not as rules governing a quasi-judicial body, but as “instructions” from the Director to his subordinates at the PTAB.

That shift changed everything.

Because the Director is the statutory decisionmaker, and because the Fintiv instructions did not bind the Director himself, the court held they were merely “general statements of policy” — expressly exempt from APA notice-and-comment requirements.

The logic was straightforward but sweeping: Only rules that bind the Director’s own discretion could qualify as substantive. Guidance the Director gives to others about how to exercise his discretion does not.

No Right to Institution Means No APA Hook

The Federal Circuit reinforced its conclusion with an even broader principle: there is no legal right to IPR institution.

Congress created IPR as a discretionary regime. A denial of institution:

- Does not invalidate or alter patent rights.

- Does not prevent validity challenges in district court.

- Does not foreclose reexamination.

In short, a non-institution decision leaves a challenger in exactly the same legal position it would have occupied had Congress never created IPR at all.

Because no legal rights are altered, rules discouraging institution cannot be “substantive” in a way that triggers APA procedural protections. This reasoning significantly narrows the scope of possible APA challenges going forward.

The Irony: Apple Won the Battle, Lost the War

Apple’s goal was to cabin discretionary denials and require formal rulemaking. Instead, the litigation produced binding precedent establishing the opposite principle.

The Federal Circuit made clear:

- Institution decisions are substantively unreviewable.

- Internal guidance on how to deny institution does not require notice-and-comment rulemaking.

- Only rules binding the Director himself could potentially be substantive.

- Non-institution does not affect legal rights in a way that triggers APA protections.

Even More Discretion Today

Compounding the impact, institutional changes during the appeal centralized authority even further. Acting Director Stewart rescinded prior Fintiv guidance and restructured review procedures. Director Squires later indicated he would personally decide institution questions based on both discretionary and merits factors.

The result is a regime even more concentrated than the one Apple originally challenged — with discretionary denial no longer meaningfully cabined by the Fintiv framework.

The Bottom Line: Nearly Unbounded Authority

The practical effect of Apple v. Squires is profound.

The USPTO Director now possesses institution authority that is, for all practical purposes, nearly unbounded:

- No notice-and-comment rulemaking required for discretionary guidance.

- No substantive judicial review of denial decisions.

- No recognized legal entitlement to institution.

- Only possible limits: constitutional constraints or self-imposed restrictions.

In trying to rein in discretionary denial, Apple secured a precedential ruling that cements it. The Director’s authority over IPR institution is now clearer than ever — and broader than when the case began.

USPTO Adds Design Search Codes for Sound and Motion Trademarks

The USPTO recently updated its Design Search Code Manual to include codes for sound and motion marks. These updates make it easier for applicants to search for existing marks that are similar to theirs.

Previously, searches relied on keywords in the mark description — which could miss some relevant marks. Now, the new codes let you search by categories such as:

- Music

- Human speech

- Animal sounds

- Instruments

- Motion

For businesses or creators registering sound or motion marks, this update provides a faster and more accurate way to identify potential conflicts.

Try our FAQ page: Non-Traditional Trademarks

Do USPTO Fee Discounts Hurt Inventors’ Chances? Probably Not.

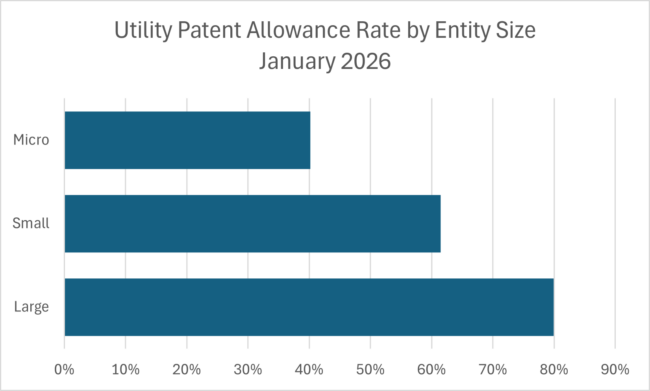

Recent USPTO data shows a sharp gap in patent allowance rates by entity size. Large entities saw about an 80% allowance rate, small entities around 61%, and micro-entities just 40%. At first glance, it’s tempting to suspect that USPTO fee discounts come with consideration discounts too.

That’s almost certainly the wrong conclusion.

Why USPTO Fee Discounts Do Not Affect Patent Examination

USPTO examiners are not incentivized based on applicant size or fee status. Entity classification affects what applicants pay—not how claims are examined. There’s no procedural hook for “micro-entity skepticism” baked into the system.

If discounted fees were driving worse outcomes, we’d expect to see some evidence of that in examiner behavior. We don’t.

The Real Reason Micro-Entity Patent Allowance Rates Are Lower

A more plausible explanation is structural, not institutional.

Micro-entities are disproportionately individual inventors. Unlike large companies, they typically lack internal screening processes that filter out weaker inventions before filing. Corporations reject many invention disclosures internally and file only after patentability and business value have both been vetted.

Individual inventors, by contrast, are closer to their inventions and often filing without:

- Broad prior-art visibility

- Repeated exposure to what doesn’t patent well

- Institutional memory of past prosecution failures

That difference alone can account for a lot of the disparity.

Why Patent Prosecution Resources and Stamina Matter

Patentability isn’t binary. Many patentable inventions still require:

- Multiple office-action responses

- Claim narrowing

- RCEs or appeals

Large entities budget for that reality. Micro-entities often don’t. When costs rise faster than perceived value, abandonment becomes rational—even for inventions that could have issued.

Lower allowance rates may therefore reflect earlier exits, not weaker inventions.

How Individual Inventors Can Improve Their Patent Allowance Odds

None of this is destiny. Inventors can materially improve their odds by borrowing a few habits from larger players:

- Be selective. Not every good idea needs a patent. File where narrower claims would still matter.

- Invest early in patentability analysis. Modest upfront diligence can prevent expensive dead ends.

- Treat the provisional as real work. Weak disclosures constrain everything that follows.

- Budget for prosecution, not just filing. Persistence is often the difference between issuance and abandonment.

- Define success realistically. A narrower, enforceable patent is often better than chasing broad claims that never issue.

What USPTO Patent Allowance Data Actually Shows

The data does not suggest that the USPTO fee discounts disfavor applicants. It suggests that scale brings discipline, resources, and endurance, all of which improve patent outcomes.

For inventors, the lesson isn’t that the system is biased—it’s that smart selection, solid drafting, and realistic prosecution planning matter just as much as the invention itself.

Check out another of our articles on entity sizes: When Trying to Save Money May Cost More

When Inventors Leave: A Hard Lesson in Trade Secret Law

A recent Federal Circuit decision, Applied Predictive Technologies, Inc. v. MarketDial, Inc. (Jan. 28, 2026), offers a blunt reminder for companies relying on trade secret protection: trade secret enforcement requires clear definition- especially after key people move on.

The Case in Brief: Applied Predictive v. MarketDial

Applied Predictive Technologies (APT) sued a competing analytics startup founded by a former McKinsey consultant who had evaluated APT’s software while working for a client. APT claimed that documents, technical guides, and client-specific data had been misappropriated under the Defend Trade Secrets Act and Utah law.

Both the district court and the Federal Circuit rejected APT’s claims at summary judgment. The problem wasn’t a lack of documents or experts, it was a lack of specificity. APT pointed to broad categories like “strategies” and “methods,” but never explained what, exactly, made those things secret, non-public, and economically valuable.

Why This Matters for Companies Relying on Trade Secrets

This case underscores a growing reality in trade secret litigation: courts will not do the plaintiff’s homework. Saying “this document is a trade secret” or dumping volumes of material into the record is not enough.

By summary judgment, companies must precisely identify what information is secret, why it is not generally known, and how its secrecy creates value.

For companies worried about losing inventors or key technical staff, the lesson is clear. Trade secrets must be defined before people leave, not retroactively in litigation. Vague claims that a departing employee “knows our approach” are unlikely to survive scrutiny.

The decision also highlights a structural risk when sensitive information is shared through consultants or third parties. APT had confidentiality agreements with McKinsey, and McKinsey had obligations to its employee, but APT could not directly enforce those obligations against the individual. Contractual protection does not automatically flow downstream.

What the Decision Means for Inventors and Founders

The ruling is equally important for inventors, engineers, and founders who move on to new ventures. The court reaffirmed a long-standing principle: employees and consultants are free to use the general knowledge and skills they acquire through their work, even when they later compete.

Learning how systems work, how problems are framed, and how technologies are evaluated does not automatically convert that knowledge into someone else’s trade secret. Former employers must identify specific, protectable information, not claim ownership over everything a person learned on the job.

That said, the line still matters. Reusing documents, code, or clearly defined confidential implementations can create real exposure. Building new systems based on experience, rather than copying prior materials, remains the safer path.

The Bottom Line on Trade Secret Enforcement

Trade secret law protects defined secrecy, not broad claims over human capital. Companies that want to retain value when inventors leave must clearly identify and guard their secrets. Inventors, meanwhile, are entitled to take their expertise with them so long as they leave the secrets behind.

The Shape of IPR Institution Under Director Squires

For a long time, inter partes review felt like gravity. If you owned a patent and someone filed an IPR, it was less a question of whether you’d be dragged into the PTAB and more a question of how painful it would be. Under Director John Squires, that gravity is still there, but it’s weaker, more selective, and far more dependent on context. For patent holders and inventors, that’s a real shift, and a meaningful one.

IPR Institution Under Director Squires: from Automatic to Selective

Let’s start with the headline: IPR is no longer automatic. Institution rates have recovered from the near-freeze of mid-2025, but they remain far below historical averages. That tells us two things. First, the PTAB isn’t “closed for business.” Second, and more important for patent owners, petitioners now have to earn their way in. Showing a reasonable likelihood of invalidity is no longer enough by itself. Director Squires is asking a different question: why should the Office spend its limited resources re-litigating this patent at all?

Let’s start with the headline: IPR is no longer automatic. Institution rates have recovered from the near-freeze of mid-2025, but they remain far below historical averages. That tells us two things. First, the PTAB isn’t “closed for business.” Second, and more important for patent owners, petitioners now have to earn their way in. Showing a reasonable likelihood of invalidity is no longer enough by itself. Director Squires is asking a different question: why should the Office spend its limited resources re-litigating this patent at all?

That change alone alters the leverage equation. The PTAB is no longer a default pressure tactic; it’s a discretionary forum. And discretion cuts both ways, but lately, it’s been cutting in favor of patent owners who have acted like responsible owners.

The Importance of Patent Age and Owner Conduct

One of the biggest signals coming out of recent decisions is how much the age of a patent and the owner’s conduct matter. Patents that have been around for a while, and that have been licensed, commercialized, or enforced, are increasingly treated as having “settled expectations.” In plain English: if you built a business around your patent, or licensed it to others who did, the Office is less inclined to yank the rug out from under you years later.

This doesn’t mean younger patents are fair game. But it does mean that ownership alone isn’t enough. The PTAB is looking at what you did with the patent. Did you put it to work? Did others rely on it? Or did it just sit quietly in a drawer?

The Risks of Inaction: Sleeping on Your Patent Rights

And that last scenario matters more than many inventors realize. Several recent decisions show that sleeping on your rights can weaken your position.

If a patent owner waits a decade to assert, tells potential infringers a license isn’t needed, or only files suit after the patent has expired, the equities start to flip.

In those cases, the PTAB has shown sympathy for challengers who reasonably believed the patent would never be enforced. That’s not a technicality, that’s a warning. Delay is no longer neutral. Sometimes it’s evidence.

Parallel Litigation and the Stakes for Challengers

Another major shift favors patent owners even more directly: petitioners now have to go all in. In cases with parallel litigation, a Sotera-style stipulation – giving up all invalidity arguments in district court if the IPR is instituted – is basically mandatory. But it’s no longer a golden ticket. It’s the price of admission, not a guarantee of entry. For challengers, that raises the stakes dramatically. For patent owners, it reduces the “heads I win, tails you lose” dynamic that plagued the system for years.

Consistency and Fair Play: PTAB’s Growing Intolerance for Gamesmanship

Layered on top of that is a growing intolerance for gamesmanship. Petitioners who argue one claim construction in court and another at the PTAB without a compelling explanation are finding the door closed. Consistency matters again. That may sound basic, but it’s a real cultural shift and one that benefits inventors who have long been forced to defend against shape-shifting theories.

IPR as Equity Practice: The Broader Shift in PTAB Strategy

Stepping back, the emerging picture is this: IPR institution now looks a lot like equity practice. The challenger still has to show a likelihood of success, but that’s just step one. The PTAB is also weighing fairness, reliance, timing, and whether administrative review is actually the right tool for the dispute. That’s a far cry from the early years of IPR, when validity challenges felt almost mechanical.

Practical Takeaways for Inventors and Small Patent Owners

For inventors and smaller patent owners, the practical lesson is simple but powerful. How you treat your patent over its lifetime now directly affects how well it can defend itself. Licensing helps. Commercialization helps. Reasonable, timely enforcement helps. Strategic silence, abandonment, or mixed signals do not.

The New Reality: IPR as a Selective Remedy, Not an Automatic Threat

IPR hasn’t gone away. But it’s no longer an automatic tax on owning a patent. It’s becoming a selective remedy, applied with judgment rather than reflex. And for inventors who view their patents as real business assets, not just litigation chips, that’s a change worth paying attention to.

Lots of news about IPR’s recently. Here were some of the earlier developments:

The Denials Will Continue Until Morale Improves

What the USPTO’s 0% IPR Institution Rate Means for Patent Holders

USPTO Proposes Major IPR Changes: What Patent Owners Should Know

Your U.S. Patent Might End Up in a German Court (Yes, Really)

When U.S. Patent Disputes Go Global

If you’re an inventor or a patent owner, you probably have a simple mental map of how patents work: U.S. patents get enforced in U.S. courts, European patents in Europe, and never the twain shall meet. That map is starting to look outdated.

A recent patent fight between BMW and a patent owner called Onesta IP shows why you may want to redraw it.

Onesta owns a portfolio of graphics-processing patents it picked up from AMD. It believes BMW infringes those patents by using Qualcomm chips in its vehicles. So far, nothing unusual. Here’s where it gets interesting: instead of suing BMW in a U.S. court over the U.S. patents, Onesta filed suit in Germany—asserting not only a European patent, but two U.S. patents as well.

If your first reaction is, “Wait… you can do that?”—you’re not alone.

Why Patent Owners Are Filing U.S. Patents in German Courts

Onesta’s strategy wasn’t a stunt. It was made possible by a recent decision from Europe’s highest court that quietly changed the rules. Under this new approach, courts in EU countries can hear cases involving non-European patents if the defendant is based there. BMW is headquartered in Munich, so Munich became fair game.

Now here’s the part patent owners really care about: German patent courts move fast. Very fast. And if they find infringement, they typically issue an injunction as a matter of course. No long balancing tests. No hand-wringing about “irreparable harm.” Infringement equals “stop.”

Compare that with the United States, where getting an injunction can feel like trying to win an Olympic decathlon—especially if you license your technology instead of manufacturing products yourself. For many patent owners, Germany looks like a shortcut around those U.S. roadblocks.

BMW Responds to International Patent Lawsuit

BMW didn’t wait around to see how this would play out. Instead, it raced to a U.S. federal court in Texas and asked the judge to step in. The court agreed, at least for now, issuing an order that blocks Onesta from using the German case to undermine the U.S. proceedings.

That tells us something important: when patent disputes go international, they can turn into jurisdictional chess matches very quickly. One side files here, the other side files there, and suddenly the fight isn’t just about infringement—it’s about which court gets to decide anything at all.

The Growing Challenge of International Patent Jurisdiction

For years, U.S. courts have refused to hear foreign patent claims, even when doing so would be efficient. The reason has been “international comity”—a polite way of saying, “We won’t step on your toes if you don’t step on ours.” The assumption was that foreign courts would treat U.S. patents with the same restraint.

Europe’s new approach puts that assumption under serious strain. If foreign courts are willing to adjudicate U.S. patent rights, U.S. courts may eventually rethink their own self-imposed limits. That hasn’t happened yet—but the door is clearly cracked open.

What Patent Owners Should Know About International Enforcement

First, forum choice matters more than ever. Where a patent dispute is filed can determine how fast things move, how much leverage you have, and whether an injunction is even on the table.

Second, international patent portfolios are no longer just defensive trophies. They can shape enforcement strategy in ways that weren’t realistic a few years ago.

Third, global patent disputes can get expensive and messy in a hurry. Multiple courts, multiple legal systems, and competing orders are not for the faint of heart.

And finally, this is another reminder that patent strategy isn’t just about getting claims allowed. It’s about thinking ahead—where your technology will be used, who might need a license, and what enforcement options you want available if things go sideways.

The short version? The patent world is getting smaller, faster, and less predictable. If your inventions are being used worldwide, your enforcement strategy should be thinking worldwide too.

We have an extensive FAQ section covering foreign filings you can check here: https://fishiplaw.com/faqs/patent-faqs/faq-foreign-filing/

We also have a video covering some of the issues with foreign patent filings.

“Configured To” Can Configure You Right Out of a Patent

Why Inventors Should Care About the Blue Buffalo Decision

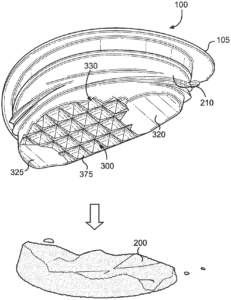

If you’re an inventor thinking about filing a patent, here’s a recent Federal Circuit decision you should care about—In re Blue Buffalo Enterprises (Fed. Cir. Jan. 14, 2026). Not because it changes the law (it’s nonprecedential), but because it exposes a trap that patent drafters fall into all the time.

The trap? Two innocent-looking words: “configured to.”

How “Configured To” Claim Construction Can Undermine Your Patent Claims

Blue Buffalo’s patent application claimed a pet food container with sidewalls “configured to be readily deformable” and a built-in tool “configured for” breaking up or tenderizing food. That sounds reasonable and it sounds structural. It also sounds like smart patent drafting. The problem is how courts usually read that phrase.

Federal Circuit Interpretation: “Configured To” Means “Capable Of”

The Federal Circuit said, once again: unless your specification clearly says otherwise, “configured to” means “capable of,” not “specifically designed to.” And that difference can make or break your patent.

Structure Over Intent: Why Patent Claims Are About the Thing, Not Your Thoughts

Here’s why.

Patent claims—especially product claims—are about structure, not intent. Courts don’t ask what the inventor meant to build. They ask what the thing is. If a prior art product can do what your claim says—even if it was built for a different reason—it can still knock out your claim.

Chief Judge Moore’s Explanation at Oral Argument

Chief Judge Moore nailed it at oral argument. Paraphrasing: if a structure “happens to actually do that,” that’s good enough. You don’t get extra credit because you intended it to do so.

That’s a big deal for inventors, because many applications quietly rely on “configured to” as a kind of magic phrase—hoping it will smuggle design intent into the claim without saying so explicitly. Courts are not buying it.

Why Blue Buffalo’s Argument Failed

Blue Buffalo tried to argue that “configured to” should mean “specifically designed to.” The judges were unimpressed. Why?

Because that would turn every patent case into a mind-reading exercise: What was the designer thinking? What was the manufacturer’s intent? That’s not how patent law works. Infringement is strict liability. Intent doesn’t matter.

How Prior Art Defeated Blue Buffalo’s Claims

So how did Blue Buffalo lose? Once the court adopted the “capable of” interpretation, the prior art fit the claims. Blue Buffalo even admitted that under that construction, the obviousness rejection stood. Game over.

Inventors often point to older cases like Aspex Eyewear and Giannelli and say, “See? ‘Configured to’ can be narrower.” True—but those cases had something Blue Buffalo didn’t: specific, concrete disclosures showing what about the structure made it especially suited for the function. Not just that it could do it, but why it did it that way.

Lesson for Inventors: Be Specific About Structure, Not Just Function

Here’s the lesson—and it’s an important one.

If a feature really matters to your invention, don’t just say it’s “configured to” do something and hope for the best. Explain what about the structure makes it work. Geometry. Placement. Relationships between parts. Physical constraints. Those are the things that earn you a narrower, more defensible claim.

The Risks of Vague Functional Language

Yes, being specific can feel risky. One reason “configured to” became popular was to avoid narrow means-plus-function claims and keep room for future variations. But vagueness has its own cost. Broad, fuzzy claims are easy to invalidate.

Blue Buffalo’s Key Takeaway for Patent Drafting

Blue Buffalo doesn’t rewrite patent law. But it reinforces a reality inventors need to understand early: functional language without structural support is a fragile foundation.

If you want “configured to” to mean more than “capable of,” you have to earn it in the specification. Otherwise, those two little words may end up configuring your patent application straight into a rejection.

Want to see some related articles on patent claims? These articles might interest you:

What Did Those Claims Consist of?

Jazz Loses the Tune: Courts Strike a Sour Note on System Patents

Patent Like You Mean it, But Also Show the Structure