NEWS

A Tale of Trademark law, the Rogers test, and Parody

The Supreme Court has been busy lately with IP cases. Just recently, the Supreme Court sided with Jack Daniel’s by ruling that the lower court got it wrong when it said VIP Products’ dog squeak toy- the Bad Spaniels Silly Squeaker was covered by the First Amendment’s free speech protection. The Supreme Court’s judgment will allow Jack Daniel’s to continue pursuing trademark infringement claims against VIP in lower courts.

How Things Got to This Point

VIP Products created an entire line of squeak toys for dogs that spoof well-known beverages in the product’s shape, design, and wording. One of those, the Bad Spaniels Silly Squeaker, spoofed Jack Daniel’s whiskey. Jack Daniel’s asked the toy maker to remove it on the grounds that the toy violated trademark law.

Trademark Law for Dummies

Trademark law exists to make sure consumers aren’t confused about the source of origin of what they are buying. So, for example, a knock-off shoe company can’t use a swoosh in the shape of Nike’s on their products. This would be a type of bait and switch where customers, relying on the quality of Nike shoes, accidentally purchase a knockoff shoe of lower quality. That would damage Nike by 1) diverting money Nike would have gotten if the customer had not been confused, and 2) causing harm to Nike’s brand if the lower quality shoes are taken to be demonstrative of Nike’s quality in general. Essentially then, trademark law is meant to serve as consumer protection.

It’s not clear how consumers would be confused into buying a doggy squeak toy if they went looking for a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, given that they would be in different parts of a store, but there is more to trademark law than just the likelihood of confusion. Trademark law also includes the concepts of dilution; which is diminishing the capacity of a mark to identify and distinguish good or services, and tarnishment; which is portraying the mark in a negative light, which ultimately threatens the commercial value of the mark.

Jack Daniel’s and VIP Sniff Each Other Out

VIP’s squeaky toy was in the shape of a Jack Daniel’s bottle, with a label that reads “Bad Spaniel, the old No. 2 on your Tennessee carpet!” The lawyers with Jack Daniel’s weren’t as amused as the rest of us by the comparison of their fine whiskey with dog poo and told VIP to clean up the mess they’d figuratively left on the carpet by hitting them with a lawsuit for trademark infringement.

VIP said the poo stays on the carpet by arguing that Jack Daniel’s infringement claim failed under the Rogers test, which protects an artistically expressive use of a trademark from infringement claims. The criteria are 1) the mark has no artistic relevance to the underlying work, or 2) the use is explicitly misleading as the source or content of the work. VIP argued that since Jack Daniel’s couldn’t demonstrate either, there was no likelihood of confusion. As for a dilution claim, Bad Spaniels was a parody, and therefore was fair use, and for those reasons, asked that the matter be summarily dismissed.

VIP Sent to the Doghouse, and then Let Out Again

The initial ruling rejected both VIP’s claims, and at the ensuing bench trial, the District court found that there was likelihood of confusion, as well as the negative association of Jack Daniel’s brand with dog poop.

The Court of Appeals however reversed the decision and sent it back to the District court to decide if Jack Daniels could satisfy either prong of the Rogers test.

Reconsidering the case, the Court found that Jack Daniel’s could not satisfy either prong of the Rogers test and decided that since the toy was a parody, it falls under the non-commercial use exclusion. VIP was cleared of infringement, and the Court of Appeals affirmed.

Bad Appellate Court! Bad Appellate Court!

Well, the Supreme Court wasn’t impressed with the Court of Appeals’ insistence that the infringement claim was subject to the Rogers test. In the Supreme Court’s opinion, “When an alleged infringer uses a trademark as a designation of source for the infringer’s own goods, the Rogers test does not apply.” VIP conceded that it had used the Bad Spaniel’s trademark and trade dress as source identifiers, and they’d done so with many similar products. Therefore, in the Supreme Court’s opinion, the only question left was whether the Bad Spaniel’s trademarks were likely to cause confusion. The Supreme Court decided that while VIP’s effort to parody Jack Daniel’s doesn’t justify use of the Rogers test, it may make a difference in the standard trademark analysis, so it sent the issue back down to the courts below.

The Supreme Court chose a narrow path. They didn’t rule on whether Rogers has merit in other contexts. They ruled it shouldn’t be used as the test in this instance.

Protecting the Little Guy… or Bad Patents?

The USPTO is considering modifications to the rules for inter partes review (IPR) and post grant review (PGR) proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Ostensibly this is to “better align… with the USPTO’s mission to promote and protect innovation and investment…” The proposed changes give the USPTO discretionary denial over who can institute challenges to patents, so that “appropriate steps” can be taken to “curb abusive actions” and “limit unnecessary and counterproductive litigation costs.”

The Federal Register detailing the proposed changes specifically mentions third parties asking for reviews of patents even when they don’t have a concrete stake in the outcome. If passed, the Director will have wider discretion to deny proceedings to “ensure that certain for-profit entities do not use the IPR and PCR processes in ways that do not advance the mission and vision” of the USPTO. The proposal also specifically mentions protecting “individual inventors, startups, and under-resourced inventors.”

The USPTO is considering adopting a “substantial relationship” test to evaluate whether a challenger is sufficiently related to a party in a challenge. If the relationship is deemed not substantial enough, discretionary denial can be applied.

On the surface, the rule changes seem laudable enough: limit unnecessary and counterproductive litigation and protect the little guy. But it is through the IPR process that patent trolls can be held accountable. It allowed members of the public to challenge bad patents, a process that trolls hate. While the proposal’s language is about protecting the little guy, it has been very easy for even the most sue-happy trolls to represent themselves as “small inventors”. While the Patent Office can pat itself on the back for protecting the little guy, they may in fact be hampering the public’s ability to challenge patent trolls.

While the mission of the USPTO is indeed to protect inventors and foster innovation, a bad patent, which is a 20-year monopoly on an invention, does the opposite. The public needs the right to challenge such patents.

Did Fair Use Get a Face-Lift?

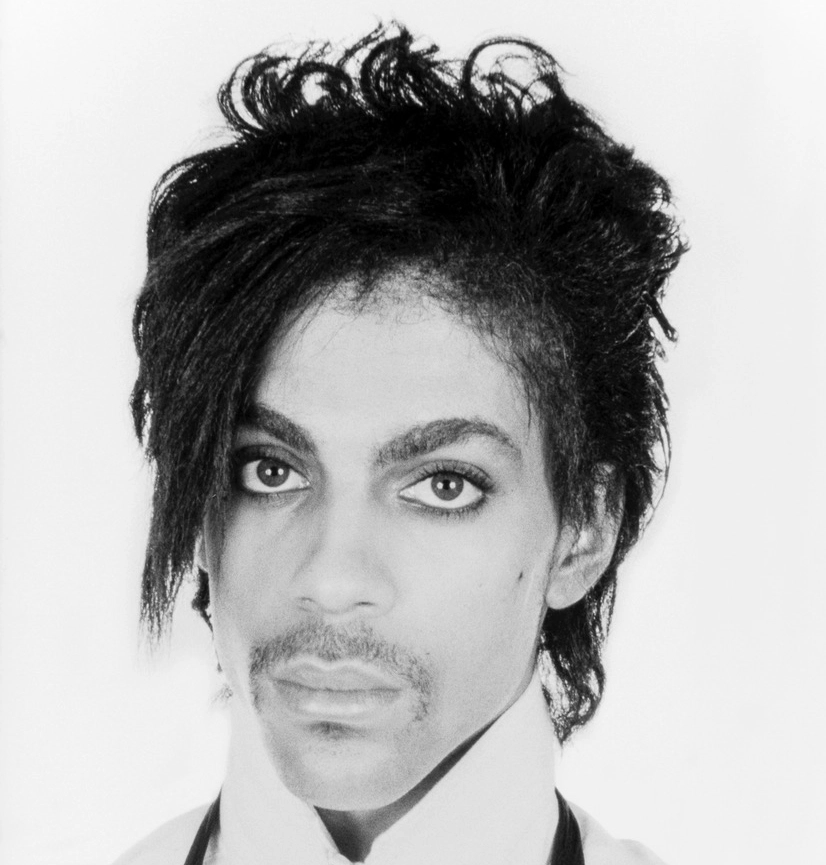

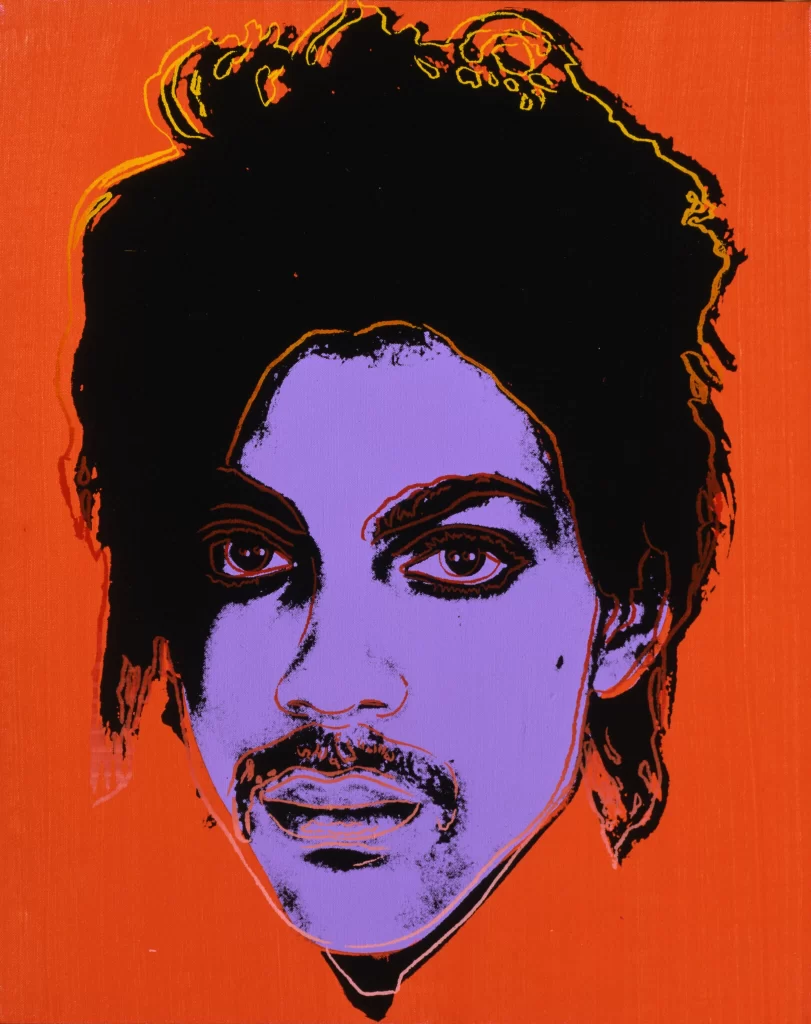

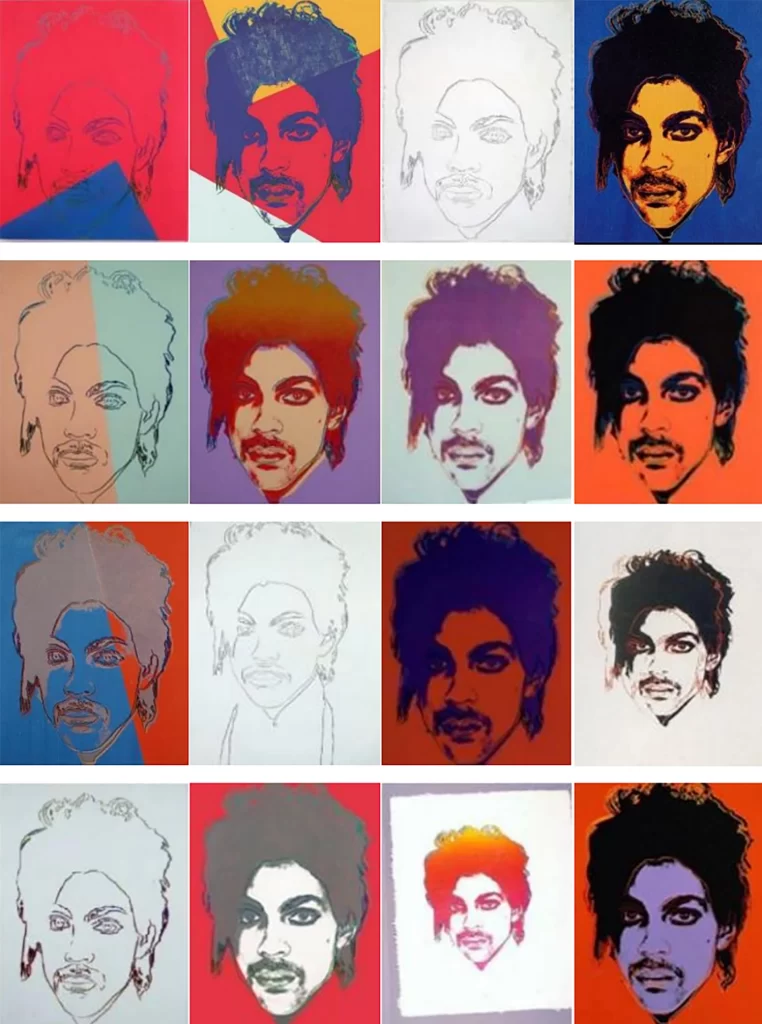

In 1981, Lynn Goldsmith photographed the music artist Prince for Newsweek magazine. 15 years later, she licensed one of those photos to Vanity Fair as a single-use artist’s reference for an illustration. The artist was Andy Warhol and he created his purple silkscreen portrait of Prince from Goldsmith’s photo. Later on, without Goldsmith’s knowledge, Warhol created a series of Prince silkscreens.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair approached the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) for a license to use one of the silkscreens, Orange Prince, for a commemorative edition of the magazine. When the magazine came out, Goldsmith became aware of the existence of Warhol’s Prince Series and sent AWF an infringement letter. AWF returned the favor by suing Goldsmith for a judgment of non-infringement under fair use.

Fair use permits a party to use a copyrighted work without the owner’s consent for purposes like reporting, teaching, or research. Each case must be decided on its own merits, but there are some general guidelines.

Factor 1 is the purpose and character of the use; is the work commercial or non-commercial, and is the use transformative- meaning it adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.

Factor 2 is the nature of the copyrighted work

Factor 3 is the amount used

Factor 4 is the effect of the use on the market

While fair use wasn’t limited to usage only in criticism, comment, reporting, teaching, etc…these examples represent the types of copying that the courts found to be typical of fair use.

However, in the 1994 landmark “Pretty Woman” case, the Supreme court, held that 2 Live Crew’s use of Roy Orbison’s song was fair use because it was transformative. It “added something new with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” After that, the transformative nature of the work took on more importance, and artists have used the transformation standard to guard against infringement claims.

In the current case, the District Court originally decided in AWF’s favor, but the Court of Appeals reversed the decision to favor Goldsmith.

The sole question before the Supreme Court was whether “‘the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes’, weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.”

The current Supreme Court expressed no opinion on Warhol’s Prince series. But the Court noted that in the Vanity Fair Prince issue, both the original photo and Warhol’s subsequent art were both used for similar purposes: “portraits of Prince used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince”, and to the point, “the copying use is of a commercial nature”. At least in this usage, whatever transformative effects AWF might claim about Orange Prince aren’t enough to overcome having stepped on Goldsmith’s commercial toes.

Perhaps the Supreme Court’s decision here will restack the priorities of Fair Use and move the commercial effect up in importance.

Lynn Goldsmith’s original 1981 photo of Prince.

Andy Warhol’s purple silkscreen print of Prince.

Warhol’s Prince series of silkscreens.

PCT Application Video

We have uploaded a new video talking about the issues involved in enforcing patents. You can find the video on YouTube here as part of our ongoing FishFAQ series of explanations of intellectual property.

We have also included these videos as part of our FAQs on the Patent FAQs sections on Types of Patents and Foreign Filings.

Right-to-Practice Video

We have uploaded a new video covering the Right-to-Practice. Having a patent on your invention gives you the right to exclude others from practicing your invention, but not necessarily the right to make and sell the invention. Find out why in this short video.

This video has been included in our Patent FAQ section on Right to Practice, and you can find all our FishFAQ videos on our YouTube Channel.

Patent Enforcement Video

We have uploaded a new video talking about the issues involved in enforcing patents. You can find the video on YouTube here as part of our ongoing FishFAQ series of explanations of intellectual property.

We have also included these videos as part of our FAQs on the Patent FAQs section on Enforcement.

Invention Disclosure video

We have a new FishFAQ video out covering Invention Disclosures. You can view it to the right, or find it on the relevant Invention Disclosure section on our Patent FAQs page.

You can find all our FishFAQ videos on our YouTube channel.