NEWS

When a Patent Case Is Really a Personhood Case

The DABUS Litigation Is a Personhood Fight Disguised as a Patent Fight

Dr. Stephen Thaler has lost another case trying to have his DABUS AI system recognized as a patent holder—this time before the Canadian Patent Appeal Board. Each loss cites essentially the same reason: inventors must be natural persons under the law.

At first, this may seem puzzling. However, the point isn’t about intellectual property at all.

A Wired article explains that “one of Thaler’s main supporters wants to set precedents that will encourage people to use AI for social good.

But Thaler himself says his cases aren’t about IP—they’re about personhood. He believes DABUS is sentient.

Photo source: https://aidecoded.com/project/dr-stephen-thaler/

The lawsuits are a way to draw attention to the existence of what he considers a new species. ‘There is a new species here on earth, and it’s called DABUS.’”

Later, the article notes that Thaler “seems exasperated that journalists have tended to focus on the legal aspects of his cases.”

Why AI doesn't need patent rights to innovate

Legal protections currently apply to humans to encourage innovation. The patent system grants rights to patent holders so that, if their intellectual property is infringed, they can seek financial compensation through the courts. Yet, if an AI system were truly sentient and invented something, would it need such encouragement? Would compensation be paid to the AI if a court ruled in its favor? The answers appear obvious: no, and no.

Therefore, there is no practical reason to give AI systems IP protection. Still, that isn’t Thaler’s mission. His stated goal is to have his system recognized as sentient and to expand the definition of personhood.

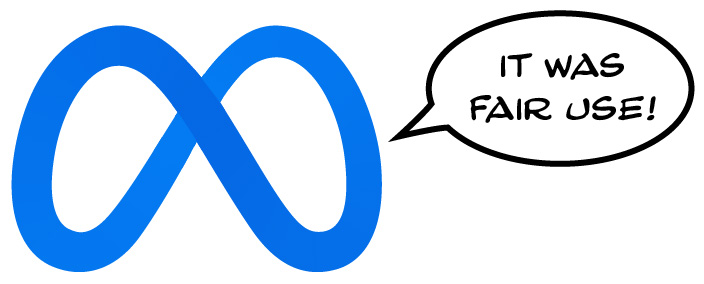

AI Training, Fair Use, and Meta

What Is Fair Use?

We recently covered the Copyright Office’s report on AI training and fair use. Fair Use is a part of copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted materials. It applies when usage occurs under certain conditions, without the copyright holder’s permission.

How AI Training Works

AI “training” uses data, including copyrighted works, for the AI to learn patterns. This data teaches models how to generate new text, images, or other outputs.

The Meta Lawsuit

Thirteen authors sued Meta for copyright infringement. The judge ruled the plaintiffs failed to show that Meta’s outputs were substantially similar to their works.

He noted that copying protected works without permission is generally illegal. However, the plaintiffs did not prove that Meta’s use caused market harm.

Why the Court Found Fair Use

In this case, using copyrighted material was considered fair use. This decision was based only on insufficient evidence of market harm. It does not settle the broader question of AI training legality.

Remaining Claims Against Meta

A separate claim alleges Meta unlawfully distributed copyrighted works. That claim was not dismissed and will continue through the courts.

Judge’s Comments on Meta’s Defense

The judge rejected Meta’s public interest argument for using copyrighted material. He called Meta’s claim that blocking the works would halt AI development “nonsense.” He added that if the books were truly essential, Meta should have licensed them.

What This Means for the Future

Although Meta won this case, stronger claims or better evidence could change outcomes. This ruling does not provide blanket permission for AI companies to use copyrighted works.

Other articles on LLM training and Fair Use: Copyright Office Report on AI Training and Fair Use

AI and Copyright: Court Rules Against Fair Use in Training AI Models

When Trying to Save Money May Cost More

The USPTO offers significant fee discounts for small and micro entities. In particular, small entities include individuals, businesses with up to 500 employees, or non-profits.

Meanwhile, micro entities meet small entity requirements and have no more than four prior applications. Additionally, they must earn less than $241,830 per year. They also cannot assign or license inventions to entities exceeding that income limit.

As a result, small entities get a 60% reduction on most patent fees, while micro entities enjoy an 80% reduction.

However, these discounts sometimes lead applicants to claim small or micro status incorrectly. To address this, the USPTO now enforces penalties for false entity claims. Fines are at least three times the fees that should have been paid.

Furthermore, the Patent Office issues notices for payment deficiencies and sends orders to show cause why the fine shouldn’t apply.

For a related article: Do USPTO Fee Discounts Hurt Inventors’ Chances? Probably Not.

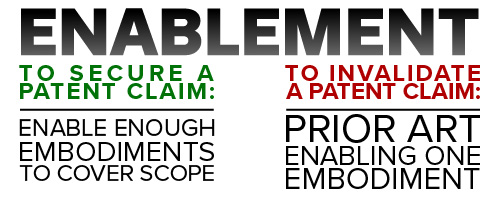

Enablement and Prior Art: What Agilent v. Synthego Teaches Us About the Limits of Patent Protection

Enablement Depends on Context

In patent law, “enablement” is critical. However, the required detail varies depending on your goal—getting a patent or invalidating one.

This distinction became clear in Agilent Technologies v. Synthego. The principle is simple but powerful: To secure a patent claim, you must enable enough embodiments to cover its full scope. Yet, to invalidate a claim, you only need prior art enabling one embodiment. This rule isn’t new, but the case clarifies it sharply.

The Two Faces of Enablement

Under Section 112, inventors must enable the full scope of their claimed invention. This prevents overbroad patents that exceed the disclosure.

You cannot describe one version of an invention and claim all variations. Instead, you must teach the public how to make and use everything claimed.

The Supreme Court reinforced this in Amgen v. Sanofi. There, a broad antibody patent was invalidated because it disclosed only a few examples. The rest required undue trial and error, which the Court rejected.

By contrast, Agilent v. Synthego draws a sharp line. Anticipatory prior art—references that can invalidate a patent—does not need to enable every version. It only needs to enable one working embodiment.

A Research Proposal as Prior Art

Agilent’s patents covered chemically modified guide RNAs (gRNAs) that resist degradation in CRISPR gene editing.

Synthego challenged them using an abandoned Pioneer Hi-Bred application. This reference described broad theoretical possibilities for modifying gRNAs, but:It contained no proven examples.

- It proposed quadrillions of combinations.

- It was ultimately withdrawn after failing to work.

Agilent argued the reference was not enabling, likening it to Amgen’s vague disclosures. However, the court disagreed. The difference is simple: Amgen concerns patent applications, while Agilent addressed prior art. The disclosure bar is lower for invalidation.

Why This Matters

The court’s approach creates a clear firewall between two standards:

- Section 112 enablement: You must enable your full claimed scope for a valid patent.

- Prior art enablement: A reference must only enable a single working embodiment to defeat novelty.

This distinction significantly affects patent strategy and litigation.

The Power of Prophetic Prior Art

The Pioneer Hi-Bred application never worked and was abandoned. Most examples were prophetic and unproven. Yet the court ruled that if even one example is enabling, a patent can be invalidated. This shows prophetic prior art can be surprisingly powerful.

Key Takeaway

If you seek a patent, you face the high Amgen enablement standard. You must teach others to make and use your invention fully.

However, to invalidate another’s patent, even speculative, abandoned prior art can suffice—so long as it enables one embodiment.

Agilent v. Synthego teaches us this: In patent law, not all enablement is equal.

For some related articles on the effect of prior art during litigation, consider these: What Did Those Claims Consist Of?

Generic Drug Label Doesn’t Induce Patent Infringement Just by Listing Optional Refrigeration

Jazz Loses the Tune: Courts Strike a Sour Note on System Patents

Federal Circuit Draws New Limits on Injunctions and Orange Book Listings

In a decision likely to affect the pharmaceutical industry, the Federal Circuit ruled in Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Avadel CNS Pharmaceuticals, LLC. The court clarified limits on injunctive relief and patent listings under the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Notably, the May 6, 2025 ruling made one point clear. Even when infringement is found, courts cannot block certain regulatory activities. That remains true if those activities fall within the Act’s “safe harbor” provision.

A Closer Look at the Dispute

Xyrem, GHB, and a Patented Distribution System

The case centered on Jazz’s narcolepsy drug, Xyrem. The drug contains GHB, a powerful sedative with known abuse risks.

To manage those risks, Jazz patented a single-pharmacy distribution system. That system tracks and controls how Xyrem is dispensed.

Meanwhile, Avadel sought FDA approval for FT218. Like Xyrem, it is GHB-based. However, FT218 uses a once-nightly dose and a different distribution approach.

The NDA Filing and Orange Book Challenge

When Avadel filed its New Drug Application, the FDA required a patent certification. That requirement stemmed from Jazz’s patent being listed in the Orange Book.

Jazz then sued Avadel for infringement. In response, Avadel challenged the Orange Book listing itself.

Specifically, Avadel argued the patent did not claim a drug. Nor did it claim a method of using one. Those, however, are the only patents eligible for listing.

The District Court Agrees with Avadel

The district court sided with Avadel. It found Jazz’s claims covered a “system,” not a drug or method of use.

That distinction proved decisive. Under Hatch-Waxman, only drug compositions and methods of use qualify for Orange Book listing.

As a result, the court ordered Jazz to delist its patent. Jazz then appealed.

The Federal Circuit Affirms the Delisting

Why System Claims Still Are Not Method Claims

On appeal, Jazz raised two main arguments. First, it claimed the patent covered a method of using Xyrem. Second, it argued FDA regulations supported broader listing categories.

The Federal Circuit rejected both points. In doing so, it emphasized several principles:

- Method claims must recite specific steps.

- A system that enables use is not itself a method.

- FDA regulations do not override patent-law fundamentals.

- Prescribing conditions do not convert systems into methods of use.

Accordingly, the court upheld the delisting order.

Clinical Trials Remain Protected by the Safe Harbor

Jazz also sought to stop Avadel’s clinical research activities. That effort failed.

The Federal Circuit was unequivocal. Even where infringement exists, courts cannot block protected research.

This includes clinical trials and open-label extensions. If those activities fall within the Hatch-Waxman safe harbor, they may continue.

That protection, the court noted, serves a clear purpose. It promotes innovation while speeding FDA approval.

Why This Ruling Matters

Taken together, the decision reinforces a key boundary. Commercial infringement is distinct from regulatory research.

It also tightens Orange Book eligibility standards. As a result, system patents face greater scrutiny.

For brand-name companies, the message is direct. If a patent does not claim a drug or method of use, it does not belong in the Orange Book.

For generics and 505(b)(2) applicants, however, the ruling offers reassurance. It preserves the streamlined path to market. That remains true even when system-based innovation is involved.

Related articles on patent infringement: Generic Drug Label Doesn’t Induce Patent Infringement Just by Listing Optional Refrigeration

PatChat is now operational

We have added some AI functionality to our website in the form of a personalized Chat GPT-based AI agent.

![]()

You can access the chatbot at the lower righthand corner of the website. Just click on the little icon and it will open up the chatbot.

The AI is trained on Bob’s books, and the FAQs from our website, so asking it questions will be like talking to Bob himself.

Have fun with it, but don’t bother asking non-IP related questions, it’s trained to stick to IP related topics.

IP Updates in Korea

Export may constitute infringement

Korea has added exporting an invention to the list of what constitutes “practicing an invention”. This means patent holders can claim damages from overseas sales more actively.

“Before the revision, if an unauthorized third party exported patented products overseas, it was not considered patent infringement.”

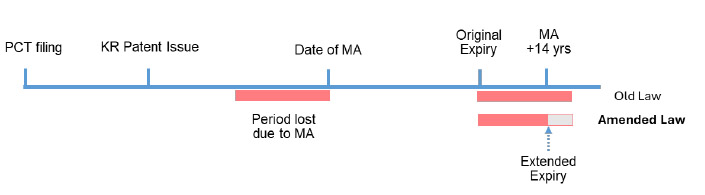

New Patent Term Extension system

Korea has also introduced two limitations on patent term extensions. The first is that a patent term can’t be extended over 14 years from the date of receipt of marketing approval. The second is that only one patent becomes eligible for patent term extension per approval.

Graph source: Hanol IP & Law newsletter

Consumer Survey Evidence

In trademark litigation, the Korean Supreme Court clarified standards for consumer surveys used as evidence of consumer recognition or perception.