NEWS

IP Updates in Korea

Export may constitute infringement

Korea has added exporting an invention to the list of what constitutes “practicing an invention”. This means patent holders can claim damages from overseas sales more actively.

“Before the revision, if an unauthorized third party exported patented products overseas, it was not considered patent infringement.”

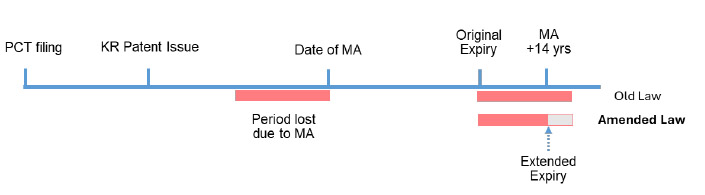

New Patent Term Extension system

Korea has also introduced two limitations on patent term extensions. The first is that a patent term can’t be extended over 14 years from the date of receipt of marketing approval. The second is that only one patent becomes eligible for patent term extension per approval.

Graph source: Hanol IP & Law newsletter

Consumer Survey Evidence

In trademark litigation, the Korean Supreme Court clarified standards for consumer surveys used as evidence of consumer recognition or perception.

USPTO discontinues the Accelerated Examination program

Given the long wait times for patent prosecution, the USPTO had offered several ways to speed the process up*. One of those, Accelerated Examination, offered the option of having the attorney certify much of the examination work in advance.

We used the accelerated examination process several times, and got quite good at it.

The USPTO puts the brakes on the Accelerated Examination program

In one instance we received notice of allowance in less than a month!

Nevertheless, it seems many attorneys did a poor job of searching (intentionally or unintentionally), so the original premise of faster prosecution was faulty.

The USPTO is discontinuing the Accelerated Examination Program.

Track One, or Prioritized Examination, is still an option for speeding up the prosecution process.

* See our FAQ page on Patent Prosecution, under the questions: How can an applicant speed up patent prosecution?

and What was accelerated examination?

The video found in those questions can be seen directly here: FishFAQ 26 Speeding Up Prosecution

Copyright Office Report on AI Training and Fair Use

Can AI Use Copyrighted Material Under Fair Use?

Can AI systems rely on the fair use doctrine when training on copyrighted works? That question sits at the center of ongoing copyright debates.

Fair use is a doctrine in U.S. copyright law. It allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission in certain situations. Courts apply a four-factor test to determine fair use. Those factors include the purpose of the use, the nature of the work, the amount used, and market impact.

However, these factors are only guidelines. Importantly, no single factor guarantees fair use on its own.

Common Examples of Fair Use

Fair use often applies to criticism, commentary, and news reporting. It also commonly applies to teaching, scholarship, and research. For example, a reviewer may quote a copyrighted book without permission when critiquing that book. However, fair use is context-specific. Uses outside these categories may still qualify, while listed purposes may still fail.

AI Training Raises New Fair Use Questions

Generative AI systems train on massive datasets. Those datasets often include copyrighted material. As a result, a key question arises. Can AI training qualify as fair use and avoid infringement? This issue was the focus of a recent study. The study was issued by the U.S. Copyright Office (USCO).

Do AI models Infringe Training Data?

The USCO report concludes that AI training implicates several exclusive copyright rights. These include reproduction and derivative work rights.

The report also examines a critical issue. Are a model’s weights themselves infringing copies?

Developers argue that models contain only numerical values. They claim these values are not copies of copyrighted works. Others disagree, pointing to AI outputs that closely resemble training data.

According to the USCO, similarity matters. When outputs are substantially similar, infringement concerns grow stronger. In those cases, the report finds a compelling argument. Copying model weights may implicate reproduction and derivative rights.

How the Fair Use Defense Applies to AI

The key issue when analyzing fair use has been whether the use is “transformative”. There is of course a spectrum. Where the output is based on a diverse dataset, it is more likely to be transformative. But where it is trained to generate outputs substantially similar to copyrighted works, then it is “at best, modestly transformative”.

Why the Human Learning Analogy Falls Short

The USCO rejected arguments that AI training is inherently transformative, because it is analogous to human learning. The report asserts that the analogy rests on a faulty premise. Fair use is not a defense for all acts if those acts are used for learning. An example was given that a student couldn’t rely on fair use to copy all of the books at a library. The analogy also breaks down technically. Humans retain imperfect, filtered impressions of works. AI systems do not. The structure of exclusive copyright rights is premised on certain human limitations.

What Comes Next for AI and Copyright

Currently, there are more than 40 cases currently pending related to the issue of AI using copyrighted materials. There won’t be a single answer whether unauthorized use is fair use. There is an ongoing discussion of some form of licensing scheme for AI training data. For now, the recommendation is to continue development without government intervention.

More copyright, AI, and Fair use articles: AI and Copyright: Court Rules Against Fair Use in Training AI Models

Revised Policy on Same-Day Dual Filings in China: Invention and Utility Model Applications

China's Two Patent Model Types

There are two types of patent protection in China: invention and utility model patents. Invention patents are similar to the US utility patents. Whereas, utility model patents are granted for technical solutions relating to shapes or structures of a product.

Same Day Dual Filing

Under Chinese patent law, when the same applicant files both an invention patent application and a utility model application for the same invention on the same day (i.e., same filing date), it is considered a same-day dual filing. Whether these applications relate to the same invention is determined based on a declaration made in the request form.

To obtain a patent for the invention, the applicant must waive the corresponding utility model right. The older practice of amending the invention application to distinguish it from the utility model is no longer permitted.

Now You Must Choose One

Previously, if the utility model right was still valid and a declaration was submitted at the time of filing, applicants had two options:

- Modify the invention application to differentiate it from the utility model, or

- Waive the utility model right.

Now, only the second option—waiving the utility model right—is allowed. This amendment is intended to streamline examination procedures and reduce the burden on both applicants and the patent office.

Implication for Applicants

At the time of filing in China, applicants should carefully assess:

- Whether filing for both invention and utility model is necessary, especially if the scopes of protection are the same.

- If the scopes are identical, whether to pursue protection via a utility model or an invention patent.

Other articles on Chinese Patent Policy: Update on the Chinese Foreign Filing License Requirement

What Did Those Claims Consist Of?

This is a very weird case interpreting “consisting of”. The Federal Circuit recently affirmed a ruling of non-infringement in Azurity Pharmaceuticals v. Alkem Laboratories. Azurity had sued Alkem for allegedly infringing patent claims related to a drinkable antibiotic.

The patent at issue—Azurity’s U.S. Patent No. 10,959,948—was a continuation of an earlier application that had been rejected due to prior art referencing the ingredient propylene glycol. To overcome that rejection, Azurity amended its claims to disclaim propylene glycol, arguing that its absence distinguished the invention from the prior art. Instead, Azurity used the more generic term “flavoring agent.”

How the Prosecution History Set the Trap

During prosecution, Azurity clearly and unmistakably argued that its claimed formulation excluded propylene glycol in order to overcome prior art. That argument worked—at least to secure allowance.

But prosecution disclaimer cuts both ways. Statements made to obtain a patent can later limit its scope. By distinguishing prior art based on the absence of propylene glycol, Azurity boxed itself in.

Why “Consisting Of” Left No Wiggle Room

In patent law, wording matters.

- “Comprising” is open-ended. It allows additional, unrecited elements.

- “Consisting of” is closed. It excludes anything not specifically listed.

Here, the claims used “consisting of,” which strictly limits the formulation to only the listed ingredients. When paired with the prosecution history disclaiming propylene glycol, the claim language reinforced a narrow construction.

The Stipulation That Didn’t Save the Claims

At trial, both parties stipulated that “flavoring agents” in the asserted claims could include substances with or without propylene glycol. Azurity argued that this meant a product containing a flavoring agent with propylene glycol would still infringe.

The district court disagreed. A litigation stipulation cannot erase a clear and unmistakable prosecution disclaimer. Even if “flavoring agent” could theoretically encompass propylene glycol, the intrinsic record controlled.

Federal Circuit Affirms Non-Infringement

The Federal Circuit agreed: Alkem’s product, which contained propylene glycol, fell outside the scope of claims that—through both language and prosecution history—excluded it.

The takeaway is simple but powerful. When you amend claims to overcome prior art—especially when using closed language like “consisting of”—you may be defining not just what your invention is, but what it can never cover.

For some other articles about patent claims: Patent Like You Mean It, But Also Show the Structure

Federal Circuit Clarifies Limits on Prosecution Disclaimer Across Patent Families

Mission Impossible: Trademarking the US SPACE FORCE

Overview of the US SPACE FORCE Trademark Dispute

In a recent ruling, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld a decision by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) to deny registration of the trademark “US SPACE FORCE.” The case offers a useful look at how trademark law intersects with national identity and public perception.

How the Space Force Name Entered the Public Domain

The term “Space Force” entered the public spotlight in March 2018, when then-President Donald Trump announced plans for a new military branch focused on space operations. By December 2019, the United States Space Force was officially established as the sixth branch of the U.S. Armed Forces.

The Timing of the Trademark Application

Just days after Trump’s 2018 announcement, intellectual property attorney Thomas Foster filed an application to register the trademark “US SPACE FORCE” for a range of goods and services on behalf of his law firm.

The timing was strategic. However, it ultimately proved insufficient to secure trademark rights.

Why the USPTO Rejected the US SPACE FORCE Trademark

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) initially refused the application under Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act. That provision bars registration of marks that falsely suggest a connection with a person, institution, belief, or national symbol.

Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act and False Association

The USPTO concluded that “US SPACE FORCE” would lead consumers to believe the mark was associated with the United States government. As a result, the Office found the mark unregistrable.

The Appeal Process Before the TTAB and Federal Circuit

Foster appealed the refusal to the TTAB, which affirmed the USPTO’s decision. He then sought reconsideration, which was denied. The dispute ultimately reached the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

When Trademark Rights Are Evaluated Under Federal Law

Foster’s primary argument focused on timing. He asserted that the trademark should be evaluated based on the facts existing at the time the application was filed, not on later developments.

Filing Date vs. Examination Date in Trademark Review

The Federal Circuit rejected this position. The court held that the proper time to assess whether a mark falsely suggests a connection is during examination, not at filing.

By the time the USPTO examined the application, the government had clearly signaled its intent to use the name for a new military branch.

The Four-Part Test for False Suggestion of Connection

Courts apply a four-part test to determine whether a mark falsely suggests a connection:

- The mark is the same as, or a close approximation of, a name or identity previously used by another person or institution.

- The mark would be recognized as pointing uniquely and unmistakably to that person or institution.

- The named person or institution is not connected with the applicant’s activities.

- The person or institution’s fame or reputation is such that a connection would be presumed.

Why US SPACE FORCE Failed the False Association Test

In this case, all four factors were satisfied. The phrase “US SPACE FORCE” clearly pointed to a well-known government entity. That entity had no connection to Foster’s law firm or its services.

Government Names and Unmistakable Public Association

The court emphasized that a mark does not need to exactly match an official government name to create a false suggestion of connection. Even though the Space Force was not formally established at filing, the name was unmistakably tied to the United States.

Why Pop Culture References Did Not Matter

Foster argued that prior fictional uses of “Space Force,” including television references, weakened the association. The court disagreed. The strong public linkage to a newly announced military institution outweighed any fictional or generic uses.

Key Trademark Law Lessons From the Space Force Case

This decision highlights how timing, context, and public perception shape trademark rights. When a mark closely aligns with national identity or government authority, registration becomes far more difficult. For businesses and attorneys alike, the case reinforces the need to consider not only what a mark says, but what it signals to the public.

Related article on Trademark principles: A Tale of Trademark Law, the Rogers Test, and Parody

Decluttering the USPTO’s Trademark Register

The USPTO recently announced it had now removed over 50,000 goods and services from the trademark register. Using ex parte expungement and reexamination proceedings, the majority of the cancellations were used against registrations linked to specimen farms.

Trademark registration requires that marks be used in real-life commerce. Specimens of the marks must be provided to the USPTO to demonstrate commercial usage prior to registration. This would serve to show a legitimate connection between the mark and the goods and services provided.

Specimen farms are websites designed to look like commercial sites. These sites list the products and the marks, which are used as specimens provided to the PTO. But the sites don’t actually sell the product.

There are filing firms, companies that assist in filing trademark applications, that created these e-commerce sites purely for the purpose of creating fake specimens.

Clearly the registry of these unused goods and services helps open up the path for legitimate companies and trademarks.

Articles on the USPTO’s ongoing efforts to clean up the registry: 52k more fraudulently filed trademark applications and registrations cleared