NEWS

A Shift in Section 101? What Recent PTAB Decisions Mean for Software Inventors

For years, Section 101 rejections have been the biggest obstacle for software and computer-implemented inventions. Recently, however, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has been reversing those rejections at a much higher rate. This suggests a meaningful shift in how patent eligibility is being evaluated at the USPTO.

What is a Section 101 rejection in Software Patent Law?

Section 101 defines what types of inventions are eligible for patent protection. Courts have long held that abstract ideas—including many business methods and software concepts—are not patentable on their own.

In practice, examiners often reject software claims by arguing that they are directed to an abstract idea and merely implemented using generic computer components, such as standard servers or networks. Under the Supreme Court’s Alice framework, claims that lack an “inventive concept” beyond that abstract idea are ineligible.

How PTAB Decisions Are Changing Section 101 Eligibility Analysis

Recent PTAB decisions indicate that the Board is no longer accepting conclusory assertions that claimed elements are “well-understood, routine, and conventional.”

Instead, the PTAB is increasingly requiring actual evidentiary support for those conclusions. This is consistent with Federal Circuit precedent such as BASCOM and Berkheimer.

Critically, the Board is recognizing that an inventive concept can exist in a non-conventional arrangement of otherwise conventional computing components. Labeling servers or networks as “ordinary” is no longer enough to establish that a particular claimed combination was routine.

What Recent PTAB Section 101 Rulings Mean for Software Inventors

This trend does not make abstract ideas patentable, nor does it eliminate Section 101 as a hurdle. But it does improve patent prospects for inventions that:

- solve concrete technical problems (e.g., latency, synchronization, security), and

- do so through specific technical architectures or system arrangements.

For many applicants, eligibility disputes may increasingly give way to more traditional patentability issues such as prior art and obviousness.

Why Software Patent Drafting Still Matters Under Section 101

This shift rewards well-drafted applications, not broad or purely functional claims. Applications that clearly explain the technical problem and the technical solution are best positioned to benefit from the PTAB’s approach.

The PTO is not reopening the door to all software patents—but it is demanding more rigor in how eligibility rejections are justified. For inventors with genuine technical innovations, that makes Section 101 a more predictable—and more navigable—part of the patent process.

Bob’s Patent Beast Comic strip series on Alice might be of interest to you as well: Alice v CLS Bank series

The changing landscape of Sec 101 rejections as seen in this post from earlier in 2025: The Harsh Reality of Sec 101 Appeals

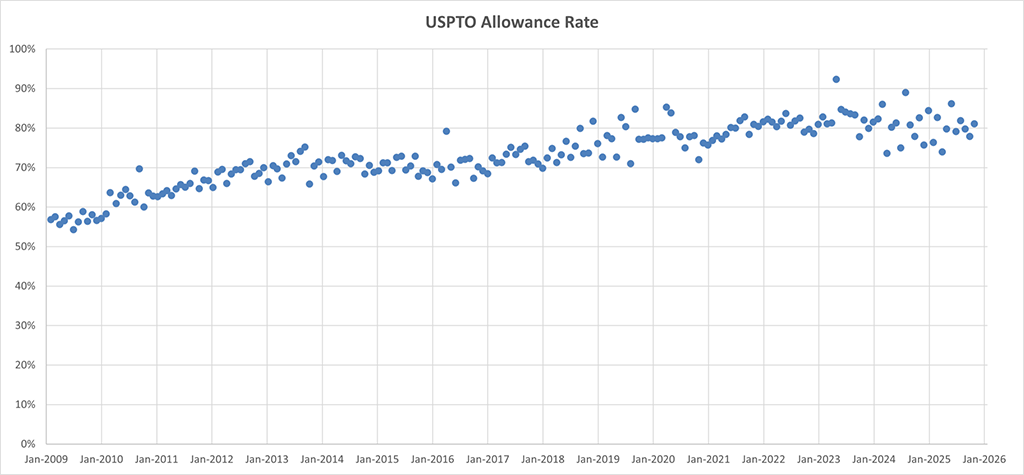

The USPTO’s Exciting Story: Almost Nothing Changed

The USPTO’s 2025 patent data points to an unusual but welcome theme: stability. Utility patent issuances held essentially flat at about 326,000—nearly identical to 2024—continuing a plateau that has persisted since 2021.

Allowance rates were also steady, generally ranging from the high-70% to mid-80% throughout the year, suggesting a predictable examination environment for applicants.

Design patents, however, tell a different story. The USPTO issued roughly 52,000 design patents in 2025, a record high and a 10% increase over the prior year. This growth reflects rising global interest—particularly from non-U.S. applicants—in protecting product appearance in the U.S. market, and highlights design patents as an increasingly important complement to utility protection.

Overall, the 2025 numbers largely reflect examination practices under Acting Director Coke Stewart and prior leadership, with any changes under newly confirmed Director John Squires likely to take time to show up in the data. For patent owners and applicants, the key takeaway is a relatively predictable utility patent landscape, alongside growing momentum and opportunity in design patent filings.

For recent news and updates from the USPTO, consider these articles:

USPTO Launches AI “Pre-Examination Search” Pilot

Why Some Business Names Can’t Be Registered Trademarks—and Why KAHWA Survived

Why Bayou Grande Matters If You’re Choosing a Brand Name

If you’re picking a business name and thinking about federal trademark protection, the Federal Circuit’s recent Bayou Grande decision offers some practical guidance—especially if your proposed name comes from a foreign language or has more than one possible meaning.

At its core, the case is about a question every brand owner eventually faces: is my business name protectable, or is it too generic to own?

What Is a Generic Name—and Why Can’t You Register It?

A generic term is the common name for a product or service itself. Examples are easy:

- You can’t register “Coffee Shop” for café services.

- You can’t register “Shoes” for footwear.

- You can’t register “Law Firm” for legal services.

Why? Because trademark law isn’t supposed to give one company exclusive rights to the words everyone else needs to describe what they sell. Generic terms belong to the public.

Once a term is deemed generic, it’s permanently unregistrable—no amount of advertising, longevity, or success can fix that. That’s why genericness is the most serious problem a brand name can have.

How the USPTO Tried to Label KAHWA as Generic

Photo source: https://stpetecatalyst.com/kahwa-opens-new-location-expands-franchising/

Photos by Ashley Morales

Bayou Grande has operated coffee shops under the name KAHWA since 2008. When it applied to register the name, the USPTO refused, arguing that:

- Kahwa can mean “coffee” in Arabic, and

- Kahwa can also refer to a type of Kashmiri green tea.

Because cafés sell coffee and tea, the USPTO concluded that KAHWA was either generic or, at minimum, merely descriptive of café services.

This kind of reasoning is not uncommon. The Office often asks: Does this word name the thing being sold, or a key feature of it? If yes, registration is denied.

Federal Circuit Ruling Protects KAHWA from Generic Trademark Refusal

The Federal Circuit reversed the refusal across the board.

First, it held that the doctrine of foreign equivalents—the rule that sometimes requires foreign words to be translated into English—does not apply when a term has a well-established alternative meaning. Here, the Board itself admitted that kahwa is widely recognized as a specific tea from Kashmir. That alone was enough to make automatic translation improper.

Second—and more importantly for brand owners—the court rejected the USPTO’s evidentiary shortcuts. There was no evidence that any café or coffee shop in the United States actually sells kahwa tea. At oral argument, the PTO conceded that point.

Without real-world evidence, the court held, the USPTO could not claim that KAHWA was generic or descriptive of café services. Speculation about what a business might sell someday is not enough.

Key Lessons from Bayou Grande for Choosing a Trademarked Business Name

If you’re evaluating a potential trademark, Bayou Grande reinforces several key principles:

- A name is generic only if consumers understand it as the name of the product or service itself—not because it has a translation or theoretical meaning.

- Foreign-language terms are not automatically generic just because they translate to something descriptive elsewhere.

- The USPTO must rely on actual marketplace evidence, not assumptions.

- Longstanding use of a name as a brand (rather than as a product label) can be powerful.

At the same time, the case is a reminder that genericness is a bright line. If your proposed name truly is the common name for what you sell, trademark law won’t save it.

Choosing a business name isn’t just a marketing decision—it’s a legal one. A name that feels distinctive to you can still trigger a genericness or descriptiveness refusal if the USPTO believes it describes the services themselves.

Bayou Grande shows that those refusals can be beaten—but only with the right facts, evidence, and strategy. That’s why involving trademark counsel early, before a name is locked in, is often the most cost-effective branding decision a business can make.

In our Trademarks FAQ section on Trademark Basics, the different “Levels of Distinctiveness” are covered in more depth.

The Denials Will Continue Until Morale Improves

IPR Denials Are Now Standard

After the recently appointed USPTO Director John Squires took the helm, IPR denials have been the standard. This of course isn’t appealing to those that want to challenge patents, so several tried an end-run around the defense by heading straight to the District Court to challenge the Patent Office’s discretionary denials. It didn’t work.

After the recently appointed USPTO Director John Squires took the helm, IPR denials have been the standard. This of course isn’t appealing to those that want to challenge patents, so several tried an end-run around the defense by heading straight to the District Court to challenge the Patent Office’s discretionary denials. It didn’t work.

IPR Refresher

In case you aren’t familiar with the IPR, it stands for Inter Partes Review. Inter partes is Latin for “between parties”, and the process allows a third party to challenge the validity of an issued U.S. patent. These reviews are done before the PTAB, and the grounds are limited to lack of novelty (§102) or obviousness (§103). They are typically filed by someone accused of patent infringement, or someone at risk of being sued.

The Federal Circuit Backs Up the PTO

Remember when, if you got a “no” from dad, you’d try your luck by asking mom?

Well Mom (the Federal Circuit) reminded everyone that Dad’s (the PTO’s) decisions on whether to institute an IPR are final and non-appealable. Meaning if the PTO says no, there’s almost nothing you can do about it, even if their reasons are inscrutable.

In Re Cambridge and Settled Expectations

The poster child for this new era is In re Cambridge Industries USA Inc. Here, Cambridge had patents that were seven and nine years old. The USPTO declared these patents to have ‘settled expectations’. Cambridge argued that this “settled expectations” idea wasn’t in the statute, wasn’t subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking, and was unfair. The court, however, was unmoved. They weren’t saying the PTO was right or wrong—they just said Cambridge didn’t have a “clear and indisputable right” to a mandamus order (that’s Latin for “we command you to do something”), and thanks to 35 U.S.C. § 314(d), which bars virtually all judicial oversight of institution decisions, the courts basically can’t command the PTO to change its mind.

Bottom line: the USPTO’s “final and non-appealable” shield is real, it’s strong, and it leaves accused infringers staring at a brick wall.

For the evolving history of the IPR, we suggest these articles:

What the USPTO’s 0% IPR Institution Rate Means for Patent Holders

How the USPTO Solved AI Inventorship by Looking the Other Way

The Federal Circuit Clarifies: Only Humans Can Be Inventors

For a while there, it looked like we had some rules.

Back in 2022, the Federal Circuit decided Thaler v. Vidal and told us, pretty clearly, that inventors under U.S. patent law have to be human beings: not corporations, not algorithms, not Stephen Thaler’s AI system, DABUS. Humans only. Full stop.

But that decision never really answered the question everyone actually cares about: what happens when humans and AI work together?

Because that’s the real world. Engineers don’t lock an AI in a room and come back later to see what it invented. Humans prompt the system, steer it, pick the good results, discard the junk, and turn outputs into working products. So how much human involvement is “enough” to count as inventorship?

USPTO Guidance Under Kathi Vidal: Drawing Fuzzy Lines

Former USPTO Director Kathi Vidal at least tried to answer that. Her guidance said, in essence: if a human made more than an insignificant contribution, then fine — that human could be named as an inventor. It wasn’t perfect, and it raised some awkward conceptual issues, but at least it gave practitioners something to work with. There was a line, even if it was a fuzzy one.

John Squires’ Approach: Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Fast forward to November 2025, and new Director John Squires has taken a very different approach. Instead of drawing lines, the USPTO has decided not to look at the map at all.

Under the new guidance, the Office isn’t going to ask how much AI was involved. It isn’t going to ask what the human actually did. If a natural person is willing to sign the inventor’s oath, the USPTO will presume human inventorship and move on. In other words: don’t ask, don’t tell.

What This Means in Practice

Practically speaking, this takes most of the bite out of Thaler. You still can’t list an AI as an inventor — that rule technically survives.

But as long as you can find a human anywhere near the project who’s willing to raise their hand and say “Yep, that was me,” you’re good to go.

And let’s be honest: finding that person is rarely hard.

Anyone who has spent time around corporate R&D knows this drill. When inventorship gets murky, someone will always step forward: the project manager; the senior engineer; the person who approved the budget; the intern who typed the prompts. It’s usually pretty easy to identify a human with some relationship to the product and prop them up as “the inventor,” even if the actual inventive heavy lifting was done elsewhere.

Efficiency vs. Accuracy: The Cost of Legal Fictions

From the USPTO’s perspective, this policy is efficient: no investigations; no philosophical debates about machine cognition; no uncomfortable questions about whether the Patent Act is built on assumptions from a pre-AI world. But efficiency comes at a cost.

What the Office is really doing here is choosing a legal fiction and sticking with it. We all pretend that the invention is human, because the paperwork says so, even when everyone involved knows the reality is more complicated. It’s inventorship theater: the forms get signed, the boxes get checked, and nobody looks too closely behind the curtain.

Thaler’s DABUS Cases vs. Real-World Innovation

Stephen Thaler’s DABUS cases forced courts to confront the issue head-on, but in an oddly artificial way. Thaler insisted that no human invented anything at all, which made the legal question easy and the facts unrealistic. Real innovation doesn’t look like that. Humans and machines work together, and the hard question isn’t whether AI can be the sole inventor — it’s how we should allocate credit when conception is shared.

The Long-Term Implications for AI-Generated Inventions

The new USPTO guidance avoids that question entirely. It preserves the appearance of human inventorship while quietly allowing AI-generated inventions to be patented, as long as everyone agrees not to talk too much about how the sausage was made.

That may feel pragmatic today. But legal fictions have a shelf life. When they stop reflecting how innovation actually happens, they don’t just simplify administration — they start to erode trust in the system itself.

Related articles about Inventorship issues: When a Patent Case is Really a Personhood Case

Getty v. Stability AI: A Win for AI—But Don’t Pop the Champagne Yet

The UK High Court has finally weighed in on generative AI and copyright, and if you’re an AI developer, the decision probably felt like a sigh of relief. If you’re a content owner, maybe not so much. Either way, this case is less “game over” and more “first inning.”

On November 4, 2025, the Court ruled largely in favor of Stability AI in its dispute with Getty Images over Stable Diffusion. Getty claimed that Stability illegally scraped millions of Getty images to train its AI model and then made that model available in the UK. The Court said: not so fast.

Training Is Not the Same as Copying

Here’s the Court’s basic logic, translated out of legalese.

Yes, Stable Diffusion was trained on copyrighted images. But no, it doesn’t keep them. Once training is done, the images aren’t sitting inside the model like photos in a filing cabinet. The AI doesn’t pull up a Getty image when you type in a prompt. It generates something new based on learned patterns.

Because of that, Getty couldn’t prove that the model—or the images it produced—were actually copies of Getty’s works. And under UK copyright law, that matters. If the copyrighted work isn’t there anymore, the model stops being an “infringing copy.”

Think of it like learning to paint by studying Monet. You don’t carry Monet’s canvases around in your backpack afterward. You just paint better landscapes. That distinction carried the day here.

But Watermarks Are a Different Story

Trademark law, however, didn’t let Stability off so easily.

The Court found that Stable Diffusion had, at times, generated images with the Getty watermark. That’s not abstract learning—that’s branding showing up where it shouldn’t. If a consumer sees a Getty watermark, they may reasonably assume Getty had something to do with the image.

And here’s the key point for AI companies: the Court pinned responsibility on Stability, not on the user who typed the prompt. If you control the training data, you own the consequences.

What the Court Didn’t Decide (And That’s the Big Part)

This case did not answer the question everyone actually cares about: is scraping copyrighted material to train AI legal in the UK?

Getty tried to litigate that issue directly, but those claims fell apart because the training happened outside the UK. So the Court never had to decide whether training itself is infringement. That means the hardest question is still sitting on the table, untouched.

The Court did make one important observation, though: an AI model can be an “article” under UK copyright law, even if it’s intangible and sitting in the cloud. Translation: if a future plaintiff can show that a model actually stores or reproduces protected works, the result could be very different.

So What Does This Mean in the Real World?

For AI developers, this is a helpful decision—but only within a very narrow lane. It says that training on copyrighted material doesn’t automatically equal infringement, at least when the model doesn’t retain or reproduce that material.

For everyone else, especially companies deploying generative tools at scale, the warning signs are still there. Trademark problems can surface quickly. Copyright law is still evolving. And the UK government is expected to weigh in again by March 2026, possibly with new rules that look more like the EU’s opt-out approach for AI training.

The Bottom Line

This case buys AI developers some breathing room. It does not buy certainty.

Some related articles on the development of AI in the copyright field: AI Training. Fair Use, and Meta

What the USPTO’s 0% IPR Institution Rate Means for Patent Holders

USPTO Director Squires Imposes 0% Institution Rate

Since October 2025, USPTO Director John Squires has personally taken control of IPR institution decisions — and the results are stark: every petition submitted under his watch has been denied. That’s right: 0% institution. Historically, the PTAB accepted about two-thirds of petitions. Now, denials come as short, unexplained notices listing only the IPR numbers. No reasoning. No analysis. Just a flat “denied.”

Loss of PTAB Transparency and Reasoned Institution Decisions

Previously, three-judge PTAB panels carefully reviewed petitions, weighing the technical merits and legal arguments, producing reasoned institution decisions that guided patent owners and practitioners. Now, with Squires juggling an entire agency of 10,000+ employees, it’s hard to imagine each petition getting anything more than a cursory glance. The lack of explanation also means no transparency and raises questions about whether decisions are substantive or just procedural.

Patent Owners Leverage Discretionary Denial Strategies

Patent owners are pushing back, citing factors like patent age, parallel district court cases, and strategic delays by challengers. Aerin Medical v. Neurent Medical is a case in point: Neurent argued that Aerin waited too long to file IPR, and that the disputes could have been raised earlier in post-grant review. These arguments reflect a broader trend: patentees are trying to use the discretionary denial process to protect their rights.

How the USPTO’s No-Institution Policy Reshapes Patent Risk

The USPTO’s new “no” policy changes the IPR landscape. Patentees can no longer rely on PTAB panels to thoughtfully review petitions, and the system’s transparency and predictability are diminished. For anyone holding patents, this signals a return to stronger patent rights and less administrative risk, but it also raises questions about whether IPR is still a meaningful alternative to litigation.

For more articles related to the ongoing IPR story, try some of these: USPTO Proposes Major IPR Changes